I found myself going down this rabbit hole after reading a recent article by Anastasia Safioleas on ABC online— Romantasy isn’t just hot, it’s shaping modern day fairy tales.

The article interviews Australian romance author and academic Dr. Jodi McAlister and some devotees/Tiktok influencers about their passion for the genre. As Dr. McAlister reminded us romance only has two rules, a central love plot and a happily-ever-after. Fantasy is about imagining impossible or improbable things.

Romantasy roughly translates as romance plus fantasy, and while the genre isn’t new, the term is. Current romantasy probably steps up the “steamy, graphic” sex compared to earlier stories, but world building is the genre’s strength. The appeal for many is the escape into a new, different and potentially wonderful world.

I was struck by the comment of one influencer, Sabine, who says she enjoys romantasy because “real life doesn’t cut it”.

“While contemporary or urban fiction is great and all, it doesn’t take me far enough. I want a full-blown escape. Send me to live with the Fae, teach me healing magic, and throw in a dangerously attractive, brooding ancient MMC who falls hopelessly in love with a seemingly ordinary female lead. Bonus points if he’s ready to burn the world down for her. It’s the ultimate fantasy.”

MMC or main male character is a modern term, used instead of protagonist or even hero. FMC is a female main character, and if you pick up a romance with two MMCs, then you know what you’re getting. But how do these terms relate to hero and heroine?

The quote above talks about an action MMC ready “to burn down the world for her”, and a “seemingly ordinary female”.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell, 1949 outlines the hero’s journey, a common narrative archetype, or story template, that involves a hero who goes on an adventure, learns a lesson, wins a victory with that newfound knowledge, and then returns home transformed.

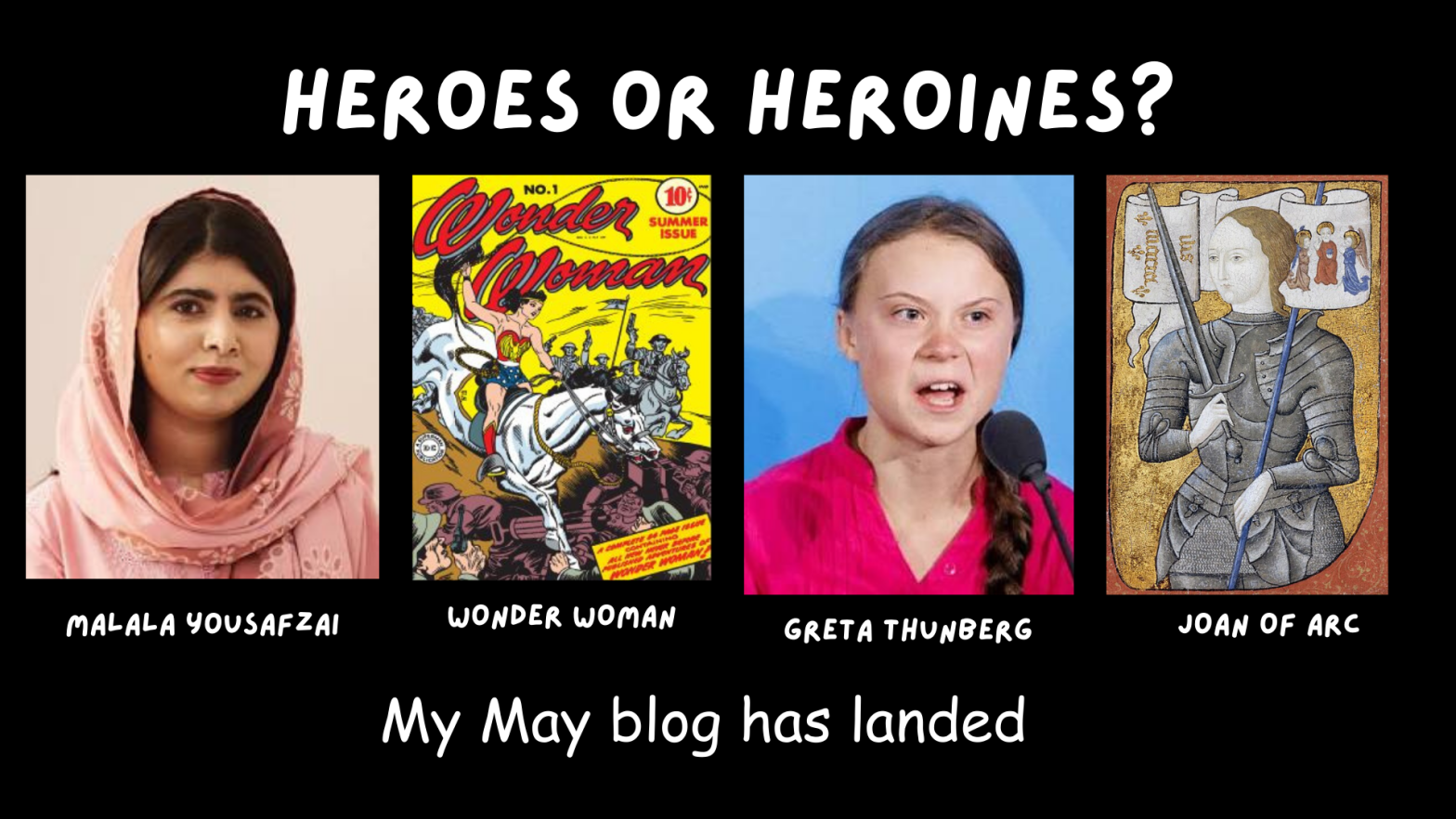

Campbell’s work started an ongoing debate especially about what a reader thinks when they say or hear the word hero or heroine. I’m simplifying this for the purposes of my blog, but a lot of scholars and individuals have been uncomfortable with the assumption that hero and heroine are interchangeable words, when in fact they imply that certain “heroic” characteristics are only associated with males.

The Afictionado blog argued in 2017 that

“we generally think of some sort of masculine Herculean or Superman-ish figure when we think “hero”

whereas the same characteristics are not associated with the word “heroine”.

In fact, a lot of people would assume a heroine simply means a main character who is a girl, or even a love interest. The word “hero is associated not just with main characters but with character types”— “active, strong, powerful”, whereas the word heroine is associated with passive terms.“

The same article quotes David Emerson who identifies this split of traits between “heroes” and “heroines” quite neatly, categorising masculine traits as “physical strength, courage, independence and self-reliance, and the tendency to use force […] as opposed to traits identified as ‘feminine’ such as empathy, nurturance, connection with community, and negotiation”.

Another article and another theory. Lewis of The Novel Smithy, March 2022 suggests that the hero’s journey and the heroine’s journey are not the same thing:

(the hero’s journey) “is primarily about overcoming physical threats—and thus attaining physical mastery”, … whereas (the heroine) “starts out in the same known world, suffering from a similar inner struggle—but, rather than set out on a physical quest, they leave home in search of their true self. This journey is all about wisdom, identity, and internal connections…”

Interestingly, the main characters in a romance usually have both external and internal story arcs, both external and internal goals, motivations and conflicts.

The definition of a hero came up for me because I’ve been editing my upcoming release An Accidental Flatmate—Choosing Family Book 5 (July 2025), and actually have a character, the main male, Casildo, say his father is his hero.

“Courageous, determined, sure of his path. He’s both an inspiration and kind to his employees. He’s also totally honest.”

I realised that for me a lot of heroic characteristics are gender neutral. For example, loyalty, honesty, bravery, courage, determination, kindness. There are also layers within these characteristics—courage can be physical, intellectual or moral. Which is most important to you when seeking a lover or a life’s companion?

Remember I noted that fantasy is about imagining impossible or improbable things—they can be sexual or romantic. Casildo’s definition of a hero works for me. I don’t actually want anyone to burn down the world for me—I can’t help feeling that innocents will get caught in the crossfire—although I want my MMC to make me burn for him.

So I find myself right back in the middle of contemporary romance grappling with what makes love work in the here and now and which heroic characteristics I want my main characters to have.

You can find me and my books here: website FaceBook Instagram

Find me on

- Instagram https://www.instagram.com/romanceauthorjen/

- Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/jenniferrainesauthor

- Goodreads—https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/22577889.Jennifer_Raines

- Bookbub – https://www.bookbub.com/authors/jennifer-raines

- Diana Kathryn Penn’s Indie Reads Aloud podcast has recordings of me reading the opening 20 mins of my books:

- Betrayal—Choosing Family Book 3 (episode 212)

- Quinn, by design—Choosing Family Book 2 (episode 208)

- Masquerade—Choosing Family Book 1 (episode 188)

- Lela’s Choice (episode 143)

- Planting Hope (episode 101)

- The Anderson Sisters (episode 54 Taylor’s Law and 80 Grace Under Fire) http://www.dkpwriter.com/indie-reads-aloud-podcast.html

You can also contact me directly via the contact page on my website if you have any other questions.